tl;dr: There's a standard for structuring a Python package and setup.py is at the heart of it.

Posted: 2017-03-06

I've pulled from several sources (see Resources below) and have mashed them together to create a brief synopsis of what I plan on doing for my first python package. I thought I'd share these findings with you. I've tried to be python ⅔ agnostic as needed.

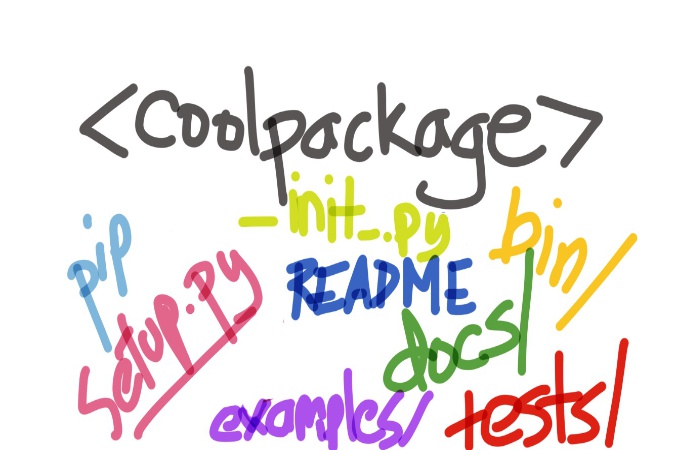

To make the most barebones package we can use the following structure (if we include the right code in setup.py this could be a pip installable package in no time!). coolname_project is the GitHub repo name and what I refer to as the base folder. This is the structure of our barebones package:

coolname_project

coolname/

__init__.py

setup.py

An example of a more common structure I've seen:

coolname_project

coolname/

__init__.py

somecoolmodule.py

command_line.py

test/

test_somecoolmodule.py

test_command_line.py

docs/

greatdoc.txt

bin/

runsomestuff.sh

examples/

snippet.py

setup.py

README

Keep reading to find out what goes in these folders and files.

A very quick example of a barebones package

To __init__.py add this:

from __future__ import print_function

def foo():

print(42)

Now we can use our brand new package in python:

>>> import coolname

>>> coolname.foo()

Add the following to setup.py (more should go here and we'll see in a bit, but this is barebones right now):

from setuptools import setup

setup(name='coolname',

version='0.1',

description='The coolest package around',

url='http://github.com/<your username>/coolname_project',

author='Your Name',

author_email='name@example.com',

license='MIT',

packages=['coolname'],

zip_safe=False)

Adding a setup.py with certain info allows us to be able to do an awesome thing: pip install our package (here, locally). In our base package folder just type:

pip install .

Congrats! You have an awesome, little package (although it doesn't do anything very cool yet - that's up to you!).

Note: the setup.py is a powerful tool and will likely contain much, much more like dependency specifications, more metadata around the package, entry points, testing framework specs, etc.

Read on...the dual-purpose README

Don't you just love reusability?

If we write our README in reStructuredText format it not only will look good on GitHub, it'll serve as the long_description or detailed description of our package on PyPi. To make sure this happens we need a file called MANIFEST.in as well. MANIFEST.in also does some more useful things (see Jeff Knupp's article in Resources below).

So, we could, for example, have in our README.rst file:

The Coolest Package Ever

--------

To use (with caution), simply do::

>>> import coolname

>>> coolname.foo()

The in our MANIFEST.in (this file does other things down the road, but for now we'll use it to include our README):

include README.rst

Summary of the folder/files in a package

This is what I've gleaned so far from guides.

Basics:

coolname/ — the source folder with sub-modules (e.g. sub-module file called dosomething.py) and containing an __init__.py file (usually empty, but req'd for installation)

coolname/test/ — package folder to hold tests; place files that begin with "test" such as test_dosomething.py so that programs like pytest can find them and execute.

NOTE: There's an alternative test folder structure where the test-containing folder is named tests (plural) and placed at the base of the package (with setup.py) - check out this doc on pytest'ing and folder structures.

setup.py — script to install/test the package and provide metadata (e.g. the long_description for PyPi) - necessary to have a pip installable package.

README — basic information on the package, how to use, how to install, etc.

bin/ - executables folder (non-py files)

Often included:

docs/ — documentation folder for the package (as .txt, .md, etc. — need to indicate this folder in setup.py if you want it in distribution)

examples/ - a folder with some samples and code snippets of package usage

scripts/ — folder for command line tools like entry points (e.g. with a main())

Makefile — a file sometimes included for running the unit tests and more

Note: if there's only one file containing all the source code you can skip creating the /coolname project folder with the __init__.py and just place the source code file in the base directory.

References and places to go for more

Check out the python-packaging guide which walks you through pip-friendly package creation here (although it's targeted for python 2).

Check out Open Sourcing a Python Project the Right Way for a detailed package dev workflow with tons of sample code and great explanations by Jeff Knupp.

Jake VanderPlas has a great blog post with videos talking about writing python packages and testing with PyTest among other things here.

Check out the do's and don'ts here for a quick "do/don't-do" synopsis around packaging in python by Jean-Paul Calderone.